Just bung a 2032 coin cell in !

A large number of small electronic devices (from flickering faux candle night lights, to the keyfob that unlocks your car doors) are powered by the ubiquitous lithium “coin cell” and, while there are other sizes in reasonably common use, that probably means a “2032” cell.

So when you come to choose a battery for your next low power radio project (maybe a miniature transmitter, maybe an ultra low

power sensor node) it’s easy to select that same familiar power cell. It’s inexpensive, they are sold through a wide variety of outlets, and it is accompanied by a wide range of clips, holders and leaded versions. It even provides a conveniently compatible-with-modern circuits 3v output

It may be an easy choice, but please: think again

These common “lithium coin cells” are based around a lithium manganese dioxide chemistry. This yields a highly stable, long shelf life cell with a decent energy density, and a usefully high 3v (peaking initially at 3.3v) cell voltage.

The problem is that the one parameter where these cells do not shine is peak current supply capability Even a larger example like the 2032 is typically rated at a few milliamps Add in the cell’s considerable internal resistance, and you have a power source that is ideal for memory backup tasks, or powering ultra low power CMOS circuits (such as calculators, or bank card verifiers) … but

unfortunately this seriously falls down when powering typical low power wireless modules. Here the peak current will be (even for 10mW types) over 10mW, with many examples in the 20-30mA range … and these modules will likely require at least 2.7v, which we will see is a problem for the 2032

Now to be fair I am not condemning the lithium manganese dioxide cell family in it’s entirety: but I am flagging up significant failings when the device being powered is a low power radio module

This is a discharge curve for a Duracell 2032

Note that for the purposes of claiming it’s 265mA/Hr

capacity, the manufacturer defines the endpoint voltage is2.0v. If your circuitry will only function to 2.7v or so (as is not that uncommon) then this is really only a 200mA/Hr cell at 200uA, while at 3mA it is unlikely to deliver more than 150mA/Hr. Increase the current drain and that internal resistance will bite further into the usable capacity.

Energizer (a competitor) rate their 2032 at only 170mA/Hr to a voltage of 2.7v if the load is a 7mA 2s pulse every 2 hrs

| Lets conduct a simple practical test. Cell under test is a middle-priced “Pifco” brand sample, bought from a convenience store in Hampshire Voltage as new, with negligible load, is 3.4v Now apply a 100R load (30mA at 3v, as representative of a typical narrowband 10mW transmitter) and the voltage drops to 3.02v immediately. This suggests an internal resistance somewhere around 12 ohms After 1 minute the on-load voltage has fallen to 2.67v After 5 minutes it is only 2.56v After the test, the open circuit voltage is 2.94v, but has risen back to 3.09v after an hour |

Again, it can be argued that short duty cycle pulsed operation will still yield a much longer lifespan, but if we imagine an again not unreasonable 25mS pulse duration, this 5 minute test (to under 2.6v) only corresponds to 12000 discrete pulses. Possibly OK for a carefully designed “push-button” fob (which is almost always off), but not for something like a low duty cycle “node” such as an environmental monitor, or for an alarm, where the power drain is constant

A perfect 230mA/Hr cell ought to be able to power a 25mA load for just over nine hours (or over 1.3 million 25mS long pulses), but the 2032 is a long way from being that “perfect” cell

| Lets repeat that test with a pair of SR44 silver oxide cells (RS own brand, rated at 160mA/Hr) Voltage as new, negligible load is 3.24v (just over 1.6v per cell) Apply a 100R load (30mA at 3v, as representative of a typical narrowband 10mW transmitter) and the voltage drops to 3.03v immediately. This again suggests an initial internal resistance somewhere around 12 ohms After 1 minute the on-load voltage has fallen to 2.86v After 5 minutes it is still 2.85v (the discharge curve of silver oxide cells is almost flat) After the test, the open circuit voltage is 3.02v, but has risen back to 3.16v after an hour |

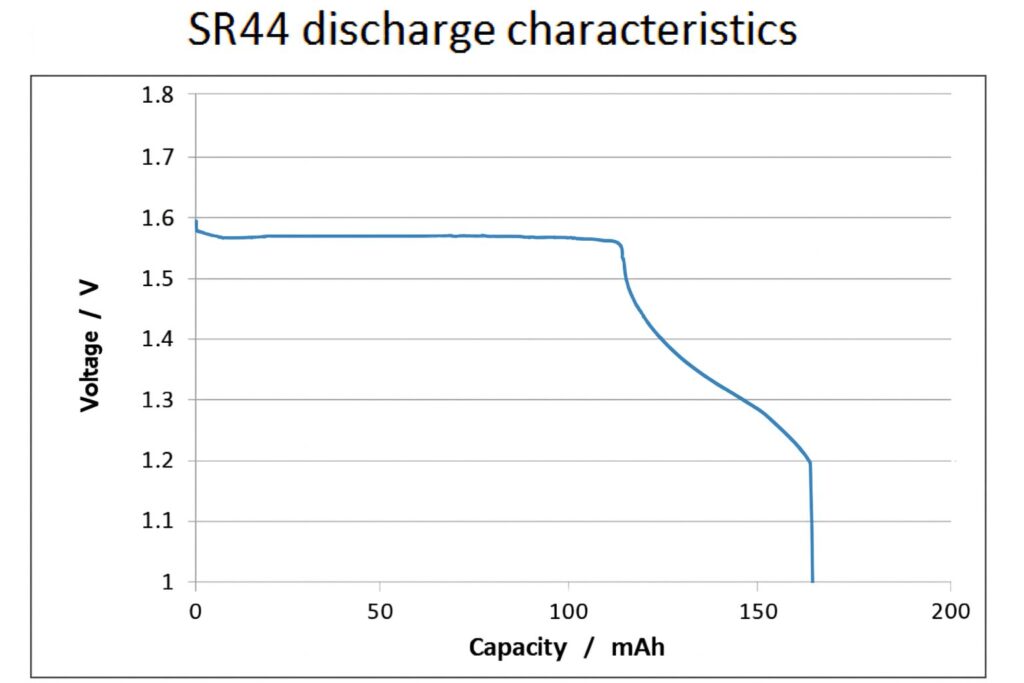

If we refer to the discharge characteristics of the silver oxide cell then we see a far “flatter” graph, with the terminal voltage holding up at around 1.55v all the way to almost 70% of the rated capacity (the graph shows a low current load, rather than our 30mA example, but is still pertinent)

For a low power wireless application, this effect alone means we will see a far longer battery life from a pair of 165mA/Hr silver oxide cells than a 265mA/hr rated 2032 lithium manganese dioxide part

The issue we are seeing here is that while the coin-cell is entirely capable of delivering it’s rated capacity into sub-milliamp loads, it falls down badly as the current is increased to something approaching that drawn by typical low power ISM band wireless modules, losing both operating voltage and usable capacity

(A further matter that is starting to raise it’s head here is that not all 2032 cells are the same. Even the two premium brands I’ve selected here have quite different data-sheets. Even the capacity varies (265mA/Hr for Duracell, but only 235mA/Hr for Energizer). If I was to throw “budget” brands into the mix I expect to see an even wider variance, while there are also relatively unusual lithium polycarbon monoflouride and lithium “organic” chemistry, cells, which are further optimised for even lower current operation)

So far we have just examined the 2032, and taken the SR44 as a hypothetical alternative in a similar size/capacity class

(In fact, if I have the space, I would be inclined to use three SR44 cells in series, and run them right down to their 1.2v discharge point to maximise capacity)

There are however a lot of battery chemistries in the market, and each of them have their own advantages and disadvantages:

We have already covered:

Silver Oxide: This chemistry has a terminal voltage of 1.55v and a very flat voltage/discharge curve. Peak current is better than a similar sized lithium, but energy capacity (especially mA/hr vs weight) is somewhat lower. Only available in small “button” sizes, and fairly costly. Self discharge is minimal and shelf life is long. Avoid confusion with alkaline cells sold in the same sizes (silver oxide SR44 vs alkaline LR44)

Lithium manganese: Nominal terminal voltage of 3v, but beware of high internal resistance, low peak current capacity and significant voltage/discharge fall off (to a 2.0v endpoint). Wide range of sizes (including our example 2032). Good shelf-life and wide operating temperature range. Relatively inexpensive Really suited only to low current tasks

However: there are other suitable types (as the reader is no doubt well aware)

| Disclaimer: We are looking at primary cells here, for low absolute power usage applications. The design considerations, and the battery technologies suitable, are VERY different if a high power usage system is being produced. In that case the rechargeable (secondary) cell is king |

Alkaline. By this we refer to the generic class of ‘one and a half volt’ common usage primary cells. Historically, these are ‘zinc-carbon’ cells, although modern construction and chemistry has resulted in far higher performance units.

Found in a range of single cell sizes (AAA, AA, C and D, plus “button” cells like the LR44) and a few higher voltage multiple cell designs (the small 9v PP3, and various small, very low capacity 6v and 12v tubular batteries often seen in older remote control designs) the alkaline cell is inexpensive, and capable of producing large pulses of current. Holders, boxes and clips for these common forms are available in a bewildering variety. Shortcomings include a relatively short shelf life (2-3 years), capacity degradation at low temperatures and at high current, unimpressive energy density and a non-constant terminal voltage (an alkaline cell delivers over 1.5v when new, but falls to 0.9v at the end of it’s life)

Although cheap, the very cheapest examples ought to be avoided, as performance can be uncertain, and leakage of corrosive electrolyte materials far more likely. Most of the higher end manufacturer’s products are interchangeable, and have similar cell capacities (despite deliberately vague advertising claims by competing makers)

Lithium thionyl As well as the LiMnO2 coin cells already described, there is also the potentially more useful, higher current capacity lithium thionyl chloride cells.

These cells have a high terminal voltage (3.5 to 3.7v, reasonably constant throughout the battery life) and(with careful choice of the specific type) moderate peak current output, with the typical maximum current for an AA cell being 55-100mA. Operating temperature range is excellent (to at least -30 degrees, with many type going to below -55) and shelf life is long. In addition to the standard AA and D alkaline sizes, lithium thionyl cells are made in 1/2 and 2/3AA, and the larger diameter 2/3A sizes. In addition to plain ‘holder’ type cells, versions are available with PCB mounting tags or axial axial wires, and occasionally custom sizes will be encountered, but oddly never an AAA size.

Primary shortcomings are high cost and limited availability (a good alkaline AA cell costs 40-60p, a lithium thionyl AA will be over £5), and a perceived chemical hazard, as although modern examples are not prone to exploding under overload like some earlier types were, they cannot be readily shipped by post.

Lithium iron disulphide. Marketed as a superior alkaline replacement, this chemistry has a terminal voltage of only 1.5v, but excellent peak current capability, high energy density (capacity), long shelf life and flat discharge curve. Only seen in AA, AAA and sometimes PP3 sizes. Expensive compared to the alkaline cells that it effectively supplants

Lithium ion (used as a primary cell). This is a recent development “borrowed” from the vape market. There are now small (theoretically rechargeable) lithium ion or lithium polymer which are marginally cheap enough to be used as disposable primary cells. They are invariably supplied in “non standard” packages, usually with wire connections and inbuilt protection circuitry, and (unless purchase volumes are very high) are costly.

Terminal voltage is 3.6v, peak current is high (especially in types intended for use in drones) and other characteristics resemble lithium thionyl. Be very careful in choosing the right part, as some have excellent self discharge rates, but not all do. Take care, as this is a new area.

There are a few other primary cells that are rarely useful for wireless applications, but which I should list: Zinc/air. Optimum for constant moderate current drain applications, these cells are rarely seen outside of hearing aid applications. They require oxygen from the air, and once the ‘seal’ is removed their self discharge is very high (unsealed shelf life is in months). Small “button” sizes only Mercuric oxide. No longer used, owing to the toxicity of the mercury, these cells were functionally equivalent to modern silver oxide cells but had a very constant 1.35v terminal voltage.

| So which cell (or battery) should be chosen? There is no “royal road” or simple executive summary, but I can offer some advice: |

If ultimate performance is critical (but cost less so) Lithium thionyl |

| If size is critical 2 or 3 silver oxide cells, or a Li ion “vape” battery |

| If cost is critical (but size is less of an issue) 3 or more alkaline cells, or maybe a pair of lithium disulphides |

Footnote : DC-DC converters

Sooner or later it’s going to occur to you that (given the availability of modern parts) one approach would be to adapt the power requirement to the battery, by means of a DC-DC converter circuit, to efficiently step supply voltages up or down. Then a low battery mean or end voltage can be made to match with the needed supply voltage into the module. A couple of alkaline cells (3v maximum, but 1.8v endpoint) could then supply a radio module and/or other circuits needing a solid 3.3v rail Simple ?

Well, yes, but (as usual) there are ‘down-sides’. Effectively three of them:

The issue with any design that integrates a switch mode supply with a sensitive radio element is therefore down to identifying the sometimes subtle ways that radio performance can be degraded and by minimizing or eliminating the possible interference issues. Receivers are inherently more at risk than transmitters (owing to the minuscule signals they handle, and the large amounts of circuit gain), but even if they remain apparently functional, transmitters can suffer sufficient interference to become non-compliant with relevant legal regulations.

If implementing a DC-DC converter based power supply:

| Endpiece: Responsible battery disposal All batteries (whatever their technology) need to be recycled at the end of their life. This is now a legal requirement Do not dispose of batteries in ordinary domestic or commercial waste. Do not crush or burn them (!!!) Collect spent batteries and recycle them. Retailers selling batteries will (by law) have disposal facilities that you should use. If you are a battery retailer, then this requirement falls on you. |

Myk Dormer for Radiometrix Ltd, August 2025